From a wargamer's perspective Hoplite warfare is grounded in mass phalanx formations in long linear lines with a stronger right wing, rather than left, with each man in these tightly packed "shieldwalls" mutually supporting the other, with the only major differences being how much armour (which is acknowledged that it became less as time progressed) and what morale class (or quality) were the troops...

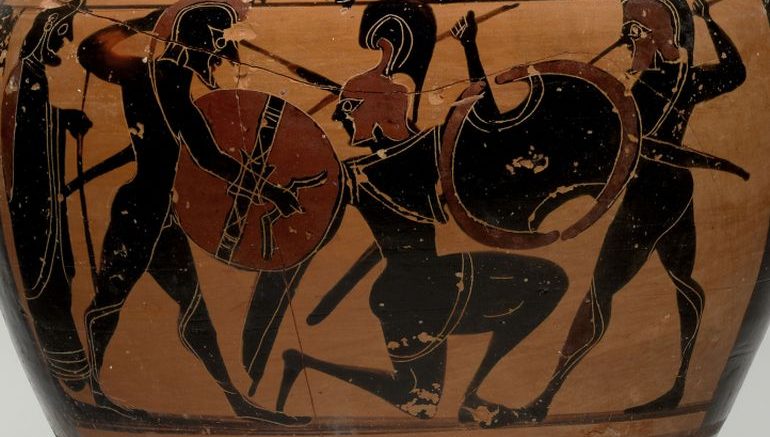

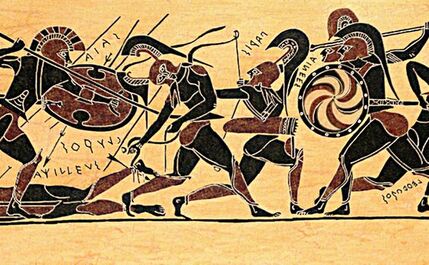

But let's look at the evidence (such that it is) and relevant historical data from the Greek Dark Age to the ascendance of Macedon some 450 years later, much of it pictorial and conjectural until the 6th Century BC

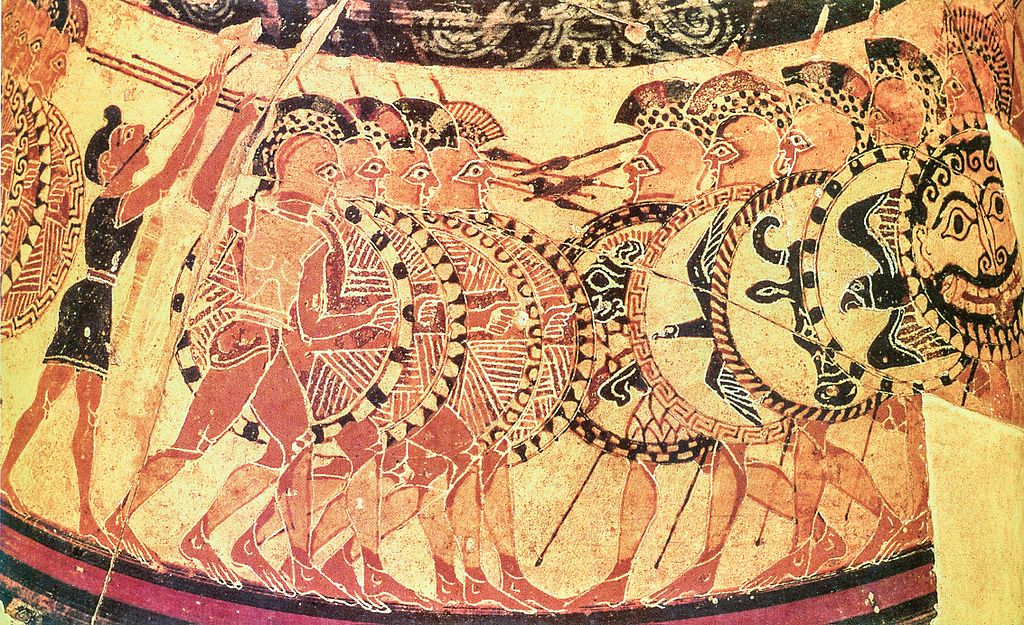

Combat in the latter stages of the Dark Age was predominantly with javelin or light spear based with soldiers fighting in a relatively loose formation, supported by light troops. From this period we start to see the military ascendance of Sparta, though not as the super troops they were to become.

However they brought a new style of fighting, a more structured approach to combat and a weapon development. So lets look at these factors and why they became popular and indeed necessary to both military power of the Greek City State as well as culturally...

As time & experience progressed though the many not-so-bloody conflicts (so City States could afford more of them) various tactics were developed and the phalanx was slowly refined and as it did so Hoplite warfare as we fight it on the wargames table came into being.

Soldiers & commanders were as able then as the modern soldier of today (we should remember all the other developments by the Greeks in this period that shows they were quite a capable & forward-thinking people). What they often did not have was technology but even so tactical finesse, though constrained until the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) did undoubtedly continue to develop.

Principally armour was reduced as formations became tighter. This intentionally or otherwise allowed larger numbers of combatants which then led to additional recruitment, training & logistical issues.... a feature that helped bring the end to the dominance of Sparta in mainland Greece. However the flexibility of the non-professional Athenians at Marathon & Salamis and the superb skills of the 300 at Thermopylae as well as the later March of the 10,000 must only touch on the overall flexibility of these troops. To say the majority were virtually untrained (excluding the more famous exceptions) is an exaggeration, though not unknown (and with frequently dire results).

If we look at the sports of the original Olympic Games (included running, long jump, shot put, javelin, boxing, pankration (a combination of boxing a wrestling with few rules) and equestrian events) they do not indicate that individual fighting skills had been discarded. Certainly at least party of Spartan military training covered the rough and tumble of disorganised individual combat and why would the most professional & organised Hoplite Army bother with these skills if it was restricted to 'Phalanx Combat'?

The hoplitodromos was the last foot race to be added to the Olympics, first appearing at the 65th Olympics in 520 BC, and was traditionally the last foot race to be held. It was traditionally the last foot race to be held. Why introduce a military running race for individuals (over a relatively short distance) during a period when a close order phalanx is becoming your main tactical deployment?

Unlike the other races, which were generally run in the nude, the hoplitodromos required competitors to run wearing the helmet and greaves of the hoplite from which the race took its name. Runners also carried the hoplites' bronze-covered wood shield, bringing the total encumbrance to at least 50 pounds. After 450 BC, the use of greaves was abandoned as a standard piece of equipment (presumably because they had already lost their military necessity).

We should not look at the Hoplite Phalanx as a simple formation that was created at some point in early Greek history but that it was an unstructured series of natural developments by different City States that complimented the societies that the citizens (and sometimes slaves) of each of the City States fought to protect. Indeed it could be said that Alexander's Army, albeit non-Greek, was the epitome of this principle & development.

The established theories:

But let's look at the evidence (such that it is) and relevant historical data from the Greek Dark Age to the ascendance of Macedon some 450 years later, much of it pictorial and conjectural until the 6th Century BC

Combat in the latter stages of the Dark Age was predominantly with javelin or light spear based with soldiers fighting in a relatively loose formation, supported by light troops. From this period we start to see the military ascendance of Sparta, though not as the super troops they were to become.

However they brought a new style of fighting, a more structured approach to combat and a weapon development. So lets look at these factors and why they became popular and indeed necessary to both military power of the Greek City State as well as culturally...

- Whilst the Loose order of fighting, typical of pretty much all tactics up until this time, was advantageous in many combat situations it was susceptible to a growing threat (mostly from the Northern Greek plains) of cavalry and, additionally, it also incurred unnecessary casualties - which could so easily be incurred by the City's elite from enemy missiles as well as a more aggressive form of fighting. So soldiers had the capability at this time of closing ranks to form mutual protection versus any enemy - in many ways switching from the aggressive to a predominantly defensive mode of combat.

- Structure (formal ranks, files, leadership, & drills) was important to this new mode of fighting and one that became known as the Phalanx... but that took many, many decades of development. But in comparison to the old style of fighting it would in most cases be more efficient on the battlefield. It should not be though that the new style of fighting lost none of its aggressive action potential... the rapid and almost certain disorganising rapid advance and closure on the enemy at the Battle of Marathon would indicate this. It is likely that the Phalanx that is played on the wargaming table never in reality existed and indeed is a simplification by both historians and rule writers alike (not that wargame rule writers have not tried to emulate the tactical flexibility of the later 'Phalanx')

- Weapon development followed, in all probability, the new style of fighting. A number of javelins and a sword probably didn't 'cut the mustard' when staying power was part of the game and fighting off, albeit light, cavalry (and indeed chariots) was a requirement and so the 'Thrusting Spear was born (although it is doubtful if that it was in the form of the longer 5th century version) to add to the defensive panoply.

- Coupled to the predominantly defensive nature, yet still more suited to a Loose structure was the retention of the javelin, for a while at least.

- In addition to the retention of the javelin an increase in personal armour would indicate a looser structure where individual fighting as a 'Homeric Warrior' would have of fought is still in order and indeed, whilst the javelin seems to have been dropped by the the latter half of the 6th Century BC, the individual protection had not (except perhaps where financial necessity required it).

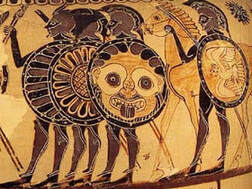

- The helmet also went through many changes from one of maximum protection, but limited hearing (of orders) to a more minimal one where not only hearing, but vision, held a greater priority. They were also easier to mass-produce.

- One major reason for this greater protection was that not only were the hoplite-equipped numbers relatively low but so were population numbers. If you lose a good section of your fittest men every time there is a border dispute then an opponent who doesn't suffer so many casualties on a regular basis at least is going to win out in the population stakes. Further to this the Greek aristocracy also ensures that the common man could not detrimentally affect the status quo quite early supported by the collective decision made during the Lelantine War (710 - 650 BC) which was to forbid the use of missile weapons in war. The thrusting Spear had come of age, within an artificial framework.

- The development of a more structured (and expensive) way of fighting also ensured the survivability of an essentially feudal nobility that controlled a stable and relatively prosperous number of City States. As historical records have proven it did not bring peace.

As time & experience progressed though the many not-so-bloody conflicts (so City States could afford more of them) various tactics were developed and the phalanx was slowly refined and as it did so Hoplite warfare as we fight it on the wargames table came into being.

Soldiers & commanders were as able then as the modern soldier of today (we should remember all the other developments by the Greeks in this period that shows they were quite a capable & forward-thinking people). What they often did not have was technology but even so tactical finesse, though constrained until the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) did undoubtedly continue to develop.

Principally armour was reduced as formations became tighter. This intentionally or otherwise allowed larger numbers of combatants which then led to additional recruitment, training & logistical issues.... a feature that helped bring the end to the dominance of Sparta in mainland Greece. However the flexibility of the non-professional Athenians at Marathon & Salamis and the superb skills of the 300 at Thermopylae as well as the later March of the 10,000 must only touch on the overall flexibility of these troops. To say the majority were virtually untrained (excluding the more famous exceptions) is an exaggeration, though not unknown (and with frequently dire results).

If we look at the sports of the original Olympic Games (included running, long jump, shot put, javelin, boxing, pankration (a combination of boxing a wrestling with few rules) and equestrian events) they do not indicate that individual fighting skills had been discarded. Certainly at least party of Spartan military training covered the rough and tumble of disorganised individual combat and why would the most professional & organised Hoplite Army bother with these skills if it was restricted to 'Phalanx Combat'?

The hoplitodromos was the last foot race to be added to the Olympics, first appearing at the 65th Olympics in 520 BC, and was traditionally the last foot race to be held. It was traditionally the last foot race to be held. Why introduce a military running race for individuals (over a relatively short distance) during a period when a close order phalanx is becoming your main tactical deployment?

Unlike the other races, which were generally run in the nude, the hoplitodromos required competitors to run wearing the helmet and greaves of the hoplite from which the race took its name. Runners also carried the hoplites' bronze-covered wood shield, bringing the total encumbrance to at least 50 pounds. After 450 BC, the use of greaves was abandoned as a standard piece of equipment (presumably because they had already lost their military necessity).

We should not look at the Hoplite Phalanx as a simple formation that was created at some point in early Greek history but that it was an unstructured series of natural developments by different City States that complimented the societies that the citizens (and sometimes slaves) of each of the City States fought to protect. Indeed it could be said that Alexander's Army, albeit non-Greek, was the epitome of this principle & development.

The established theories:

- Gradualist theory

- Rapid adoption theory

- Extended gradualist theory

Common Greek Military Terminology from the 'Classical' period

Or 'Why we might need to re-look at the way we portray "Hoplite Warfare" on the wargames table'. For the record the Greek name for the shield carried by the Hoplite is not 'Hoplon' but Aspis koilè (Aspis is the general name for shield).

Or 'Why we might need to re-look at the way we portray "Hoplite Warfare" on the wargames table'. For the record the Greek name for the shield carried by the Hoplite is not 'Hoplon' but Aspis koilè (Aspis is the general name for shield).

Greek Word |

Weapon Category |

Tactics Category |

Troop Classification |

Armour |

Cheir |

- |

- |

- |

Arm Protector |

Doration |

Light Spear |

- |

- |

- |

Dory |

Spear |

- |

- |

- |

Dromos |

- |

Charge on the run |

- |

- |

Ekdromos |

- |

'Out Runner' |

- |

- |

Hèmithoorakion |

- |

- |

- |

Half Armour (breast only) |

Hoplitès |

- |

- |

Heavily-armed soldier |

- |

Hoplon |

- |

Weapon, both offensive & defensive |

- |

- |

Hyssos |

Spear or Javelin |

- |

- |

- |

Kataphraktès |

- |

- |

- |

Suit of Armour |

Kataphraktos |

- |

- |

- |

Armoured soldier |

Knèmis |

- |

- |

- |

Greaves |

Koilè phalanx |

- |

Concave Battle Formation |

- |

- |

Koilembolos |

- |

Hollow Wedge Formation |

- |

- |

Kontophoros |

- |

- |

Spearman |

- |

Lonchè |

Spear or Javelin |

- |

- |

- |

Lonchophoros |

- |

- |

Spearman or Javelineer |

- |

Mitrè |

- |

- |

- |

Abdominal armour |

Oothismos aspidoon |

- |

Shield "shoving" or "pushing" |

- |

- |

Palton |

Javelin |

- |

- |

- |

Paramèridion |

Side-arm |

- |

- |

Thigh armour |

Peltarion |

- |

- |

- |

Light Shield |

Peltastès |

- |

- |

Shield bearing Javelineer |

- |

Pelekophoros |

- |

- |

Axe-man |

- |

Pelekys |

Battle axe |

- |

- |

- |

Pezakontistès |

- |

- |

Skirmisher, Javelineer |

- |

Phalanx (1) |

- |

- |

Close order Heavy Infantry |

- |

Phalanx (2) |

- |

- |

small group of promachoi |

- |

Polemikon |

- |

Charge! Trumpet signal |

- |

- |

Proknèmis |

- |

- |

- |

Greave |

Promachos (1) |

- |

- |

"front fighter" |

- |

Promachos (2) |

- |

- |

Heavily armed soldier fighting ahead of light missile troops |

- |

Prootostatès |

- |

- |

Front ranker |

Value |

Proptoosis |

- |

Levelling of spears to the front of the battle line |

- |

- |

Pyknosis |

- |

Close Order formation |

- |

- |

Synaspismos |

- |

Locked shield formation |

- |

- |

Systasis |

- |

- |

Light Infantry Platoon |

- |

Tattoo |

- |

To deploy |

- |

- |

Tetrarchia |

- |

Unit of 4 files |

- |

- |

Thoorax |

- |

- |

- |

Body armour |

Thyreos |

- |

- |

- |

Shield |

Xyston |

Spear |

- |

- |

- |

Xystophoros |

- |

- |

Spearman |

- |

Zeugitès |

- |

- |

Citizen financially able to become a Hoplite |

- |

Conclusions

It is likely that individual City States gradually developed their warring bands of Infantry from ill-equipped light troops combined with small groups of noble warriors (able to buy some or all of what became a full panoply of armour) and armed with spear and/or javelin and sword to larger trained bands of lesser equipped but still moderately-well armoured 'Heavy Infantry' that could still fight aggressively as well as defend themselves through forming close order and even locking shields....

When the javelin was removed from general use is debatable but it was probably either during the later stages of the Lelantine War or more likely some time after when it was realised that in the formalised style of warfare javelins were inefficient in that Units would fail to close with their opponent and the battle would develop into an inefficient firefight and/or broke up the 'Phalanx' and which ultimately prolonged the result of the battle and only increased logistical issues. It is likely that the more progressive (at this point) Spartans were the first to discard the javelin in Heavy Infantry formations.

It is also possible that due to the nature of the terrain in Greece that different types of Hoplite appeared, providing additional tactical potential on the battlefield (though this is likely to be solely reflected in lesser armour). These difference could alude to both Ekdromos and Promachos units which may have fought between or within existing units and ordered to deploy as and when the need arose.

Certainly there was a higher degree of tactical finesse only marred by technical ability of the troops under command, something that the Spartans would have mitigated earlier than most. Formal training will ensure better discipline and cooperation between units and significantly this will have only been available to the Spartans, retained units, formations on campaign and mercenary units.

Overall armies would have seen a signifiant improvement in professionalism over the centuries as well as developing tactics as new enemy troop types appeared and weapons restrictions relaxed. Control (or lack of it) would seem to be the biggest factor - but Hoplite units were still able to carry out a rapid & aggressive charge, and one that would not usually be replicated on the wargames table.

It is likely that the typically Open order style of combat of the Archaic Period was substituted by a Loose order as spears became more common and that this was further modified by lesser armoured units being able to form tight defensive formations. The movement restrictions on Close formation foot on the wargames table do seem unrealistic at best. Even the later Pike Phalanx was able to manoeuvre in a 'Loose order' on the battlefield, only tightening up when the tactical need arose.

Background Information

For more general information on an introduction to Ancient Greek History from its origins, through the Dark Age and beyond there is an interesting series of lectures on the subject by Donald Kagan available on YouTube.

Polybius and Asclepiodotus, along with other ancient military writers, provide a rich source of information on various phalanx formations and manoeuvrers. Their works help us understand the tactical flexibility and strategic thinking behind Greek and Hellenistic warfare. Here, I will explain several key formations and manoeuvrers., drawing on their writings and other historical sources.

1. The Standard PhalanxDescription:

It is likely that individual City States gradually developed their warring bands of Infantry from ill-equipped light troops combined with small groups of noble warriors (able to buy some or all of what became a full panoply of armour) and armed with spear and/or javelin and sword to larger trained bands of lesser equipped but still moderately-well armoured 'Heavy Infantry' that could still fight aggressively as well as defend themselves through forming close order and even locking shields....

When the javelin was removed from general use is debatable but it was probably either during the later stages of the Lelantine War or more likely some time after when it was realised that in the formalised style of warfare javelins were inefficient in that Units would fail to close with their opponent and the battle would develop into an inefficient firefight and/or broke up the 'Phalanx' and which ultimately prolonged the result of the battle and only increased logistical issues. It is likely that the more progressive (at this point) Spartans were the first to discard the javelin in Heavy Infantry formations.

It is also possible that due to the nature of the terrain in Greece that different types of Hoplite appeared, providing additional tactical potential on the battlefield (though this is likely to be solely reflected in lesser armour). These difference could alude to both Ekdromos and Promachos units which may have fought between or within existing units and ordered to deploy as and when the need arose.

Certainly there was a higher degree of tactical finesse only marred by technical ability of the troops under command, something that the Spartans would have mitigated earlier than most. Formal training will ensure better discipline and cooperation between units and significantly this will have only been available to the Spartans, retained units, formations on campaign and mercenary units.

Overall armies would have seen a signifiant improvement in professionalism over the centuries as well as developing tactics as new enemy troop types appeared and weapons restrictions relaxed. Control (or lack of it) would seem to be the biggest factor - but Hoplite units were still able to carry out a rapid & aggressive charge, and one that would not usually be replicated on the wargames table.

It is likely that the typically Open order style of combat of the Archaic Period was substituted by a Loose order as spears became more common and that this was further modified by lesser armoured units being able to form tight defensive formations. The movement restrictions on Close formation foot on the wargames table do seem unrealistic at best. Even the later Pike Phalanx was able to manoeuvre in a 'Loose order' on the battlefield, only tightening up when the tactical need arose.

Background Information

For more general information on an introduction to Ancient Greek History from its origins, through the Dark Age and beyond there is an interesting series of lectures on the subject by Donald Kagan available on YouTube.

Polybius and Asclepiodotus, along with other ancient military writers, provide a rich source of information on various phalanx formations and manoeuvrers. Their works help us understand the tactical flexibility and strategic thinking behind Greek and Hellenistic warfare. Here, I will explain several key formations and manoeuvrers., drawing on their writings and other historical sources.

1. The Standard PhalanxDescription:

- A tightly packed infantry formation with soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder in ranks and files.

- Each hoplite carried a large round shield (aspis) and a long spear (dory).

- Designed for frontal assaults and defensive stand-offs.

- The overlapping shields created a shield wall, providing excellent protection.

- Depth could vary from 8 to 16 ranks deep, depending on the situation.

- Developed by Epaminondas of Thebes and used at the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE).

- One wing (usually the left) was weighted with more troops and made deeper, while the other wing was held back.

- Created a powerful thrust on one side of the battlefield to break through the enemy line.

- The deeper formation could penetrate the enemy’s formation, creating a rout.

- One flank is held back or positioned at an angle to the main line.

- Prevents the enemy from flanking.

- Allows the commander to reinforce or reposition the refused flank if needed.

- Used effectively by Alexander the Great at the Battle of Gaugamela (331 BCE).

- A concave or inward-curving line.

- Encircles and traps the enemy forces.

- Maximizes the advantage of superior discipline and equipment.

- Can also serve as a defensive formation to protect the flanks and rear.

- Troops arranged in a square with the centre hollow.

- Protects against attacks from all sides.

- Used effectively for guarding baggage trains or when surrounded.

- Troops form a triangular or wedge shape, with the point facing the enemy.

- Penetrates enemy lines with concentrated force.

- Often used by cavalry but could be adapted for infantry.

- Troops attempt to encircle the enemy on both flanks simultaneously.

- Surrounds and annihilates the enemy force.

- Famous example: Battle of Cannae (216 BCE) by Hannibal, though primarily involving Roman legions.

- Combining various types of troops within the phalanx, such as light infantry, archers, and heavy hoplites.

- Increases flexibility and the ability to respond to different threats.

- Allows for combined arms tactics, integrating ranged and melee combat.

- Increasing the depth of the formation, sometimes up to 50 ranks deep.

- Increases the pushing power (othismos) during a frontal assault.

- Creates a powerful, dense block that is hard to penetrate.

- Polybius (Histories):

- Describes various formations and the tactical innovations of the Hellenistic period.

- Focuses on the importance of discipline and cohesion in maintaining phalanx effectiveness.

- Describes various formations and the tactical innovations of the Hellenistic period.

- Asclepiodotus (Tactica):

- Provides a detailed account of Hellenistic military tactics and formations.

- Explains the theoretical underpinnings of different phalanx configurations and their applications.

- Provides a detailed account of Hellenistic military tactics and formations.

- Aelian (Tactica):

- Another key source on Greek and Hellenistic tactics, complementing Asclepiodotus.

- Emphasizes the practical aspects of deploying and manoeuvring the phalanx.

- Another key source on Greek and Hellenistic tactics, complementing Asclepiodotus.

- Xenophon (Hellenica, Cyropaedia, Anabasis):

- Offers insights into the practical use of the phalanx and other formations during his campaigns.

- Highlights the importance of leadership and flexibility in battle.

- Offers insights into the practical use of the phalanx and other formations during his campaigns.

- Arrian (Anabasis of Alexander):

- Details the campaigns of Alexander the Great, providing examples of various phalanx manoeuvrers. in action.

- Illustrates the integration of phalanx tactics with cavalry and other forces.

- Details the campaigns of Alexander the Great, providing examples of various phalanx manoeuvrers. in action.